Design Is a Process, Not a Moment

- mojgan aghamir

- Feb 1

- 3 min read

Updated: Feb 1

How early decisions quietly lock in cost, risk, and complexity.

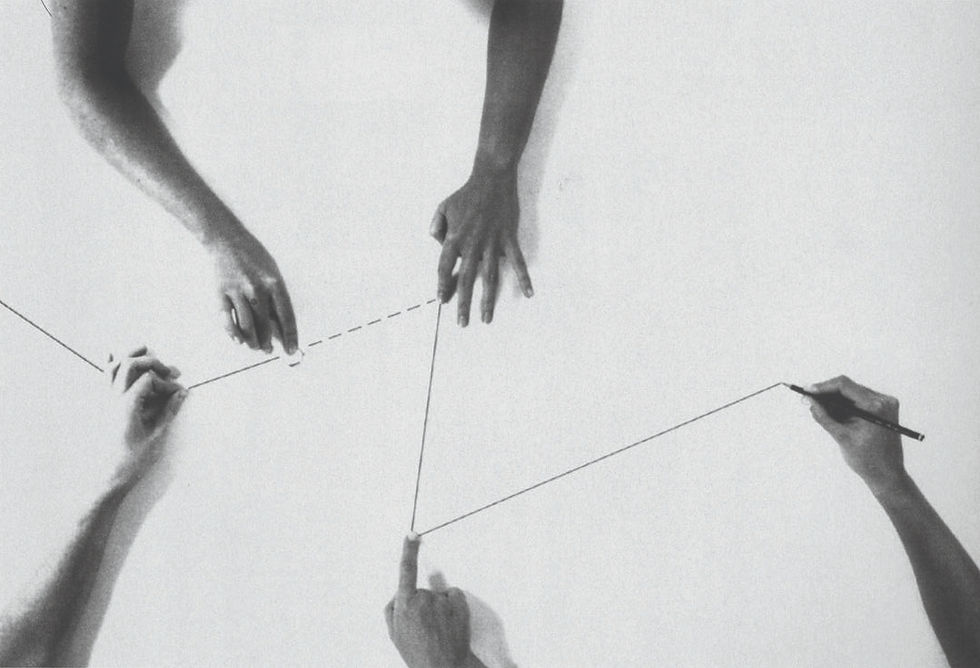

Architecture is often described as a moment of inspiration—the sketch, the concept, the big idea. That image is compelling, but it’s also misleading. In practice, design is not a single moment of clarity. It is a sequence of decisions, many of them small, that accumulate and harden over time.

What determines the success of a project is rarely the strength of one idea. It is the discipline of the process that carries that idea forward.

The myth of the decisive design moment

Early in a project, decisions feel light. Plans are flexible, details are unresolved, and change appears inexpensive. This creates the illusion that nothing is final yet. In reality, many of the most consequential choices are made precisely during this phase—often without being recognized as such.

Site assumptions, program alignment, structural direction, grid logic, and envelope strategy may be framed as “placeholders,” but they quickly become defaults. Once consultants begin working, budgets are tested, and schedules are set, those placeholders solidify. Reversing them later is possible, but rarely without cost.

The danger is not making early decisions. The danger is making them casually.

How early assumptions turn into constraints

Every project begins with incomplete information. That is unavoidable. What matters is how assumptions are treated.

When assumptions are left unexamined, they quietly shape everything that follows. A structural system chosen for convenience limits spatial flexibility. A planning layout set too early constrains mechanical coordination. A budget model based on optimism pressures later documentation.

These constraints rarely announce themselves. They emerge months later as coordination conflicts, value engineering exercises, or rushed compromises—often blamed on construction or permitting, when the root cause lies much earlier.

By the time issues surface, the project no longer has room to absorb them cleanly.

Cost, risk, and complexity are set early

It is well understood—but often ignored—that the ability to influence cost is greatest at the beginning of a project. Less discussed is that risk and complexity follow the same curve.

Cost increases when systems are misaligned

Risk increases when responsibilities are unclear

Complexity increases when decisions are deferred without structure

When early design phases lack discipline, later phases become reactive. Documentation grows heavier, coordination meetings multiply, and contingency replaces clarity. None of this improves architecture. It only consumes energy that could have been directed toward quality.

A strong process does not limit design. It protects it.

Where architects lose control without noticing

Loss of control rarely happens all at once. It happens incrementally.

It happens when scope boundaries blur “just to keep things moving.”

It happens when coordination is assumed instead of confirmed.

It happens when drawings advance faster than decisions.

Over time, the architect shifts from author to problem manager—responding to conflicts instead of shaping outcomes. By the construction phase, design intent may still exist, but the ability to defend it has eroded.

This is not a failure of creativity. It is a failure of process.

Process discipline as a design tool

Process is often treated as administrative overhead—something separate from design. In reality, it is one of the architect’s most powerful tools.

A disciplined process:

Forces clarity before commitment

Aligns consultants early

Makes tradeoffs explicit

Reduces downstream rework

It creates space for better design decisions, not fewer ones.

Importantly, process discipline does not mean rigidity. It means intentional sequencing—knowing which decisions must be resolved now, which can wait, and which must remain flexible.

A practical takeaway

Design quality is not protected by talent alone. It is protected by structure.

Architects who treat design as an ongoing process—rather than a singular moment—retain control longer, reduce unnecessary risk, and produce work that is calmer, clearer, and more resilient.

The strongest projects are not those with the most dramatic beginnings. They are the ones whose early decisions were made carefully, tested honestly, and carried forward with consistency.

Comments